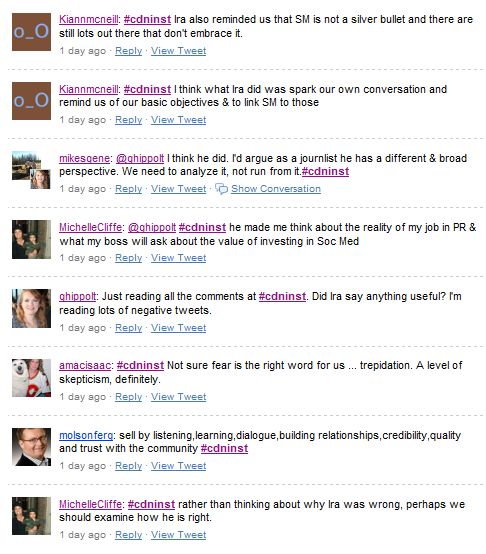

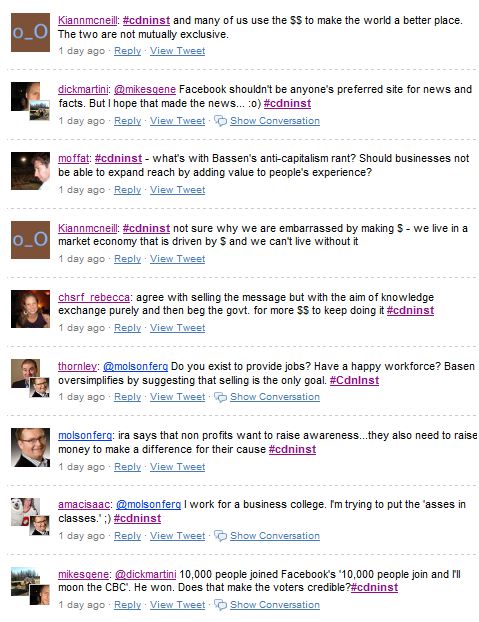

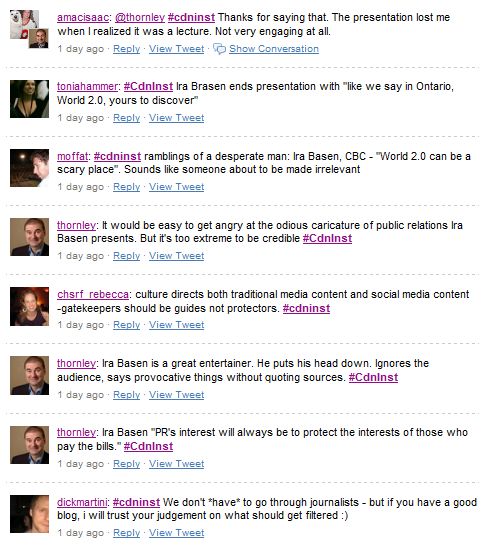

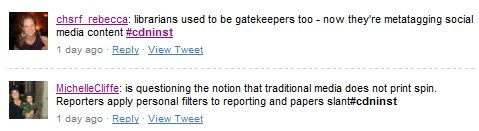

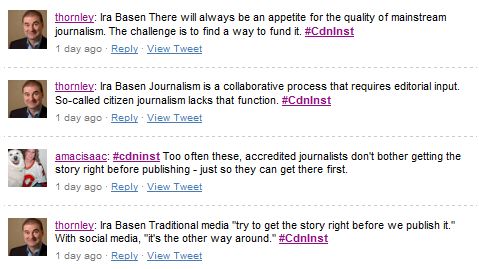

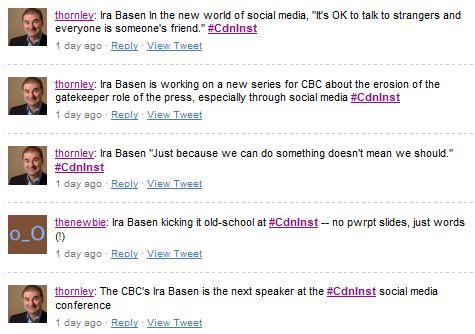

On Monday, I wrote a post about the conversation that had started around Ira Basen‘s presentation to the Canadian Institute Conference on Social Media.

Ira has provided me with his speaking notes and agreed that I can publish them on ProPR.

I found a lot of value in Ira’s remarks. I also found a lot I disagreed with. Regardless of whether you agree with everything he has to say, his presentation is well worth reading and considering.

———————

Ira Basen’s Canadian Institute speech

Ira Basen’s Canadian Institute speech

Dec. 3 2008

I know that you have spent most of the past two days dealing in very practical

suggestions about using social media. But I’m not a PR person, and I have often be

accused of being not very practical, so for the next little while, while you’re digesting

your lunch, I’m going to offer you something a bit different. I’d like to try to put some of

the practical lessons you’ve learned into a larger framework, to see where what you do as

communicators, and what I do as a journalist, fit in this brave new world that I like to call

World 2.0.

There will probably be no practical lessons learned in the next half hour or so, but I’m

hoping that at the end of it, you will at least understand what I think some of the big

questions are that we need to ask. Sometimes I think we can get swept up in the tide of

technological change which is coming at us so rapidly that we don’t have time to think

about what it will all mean.

For example, as some of you may know, last week Steve Rubel was in town. He is the

digital guru at Edelman’s in New York. And he recently predicted that by 2014, there

will be no more of what he calls “tangible media” – meaning no more books,

newspapers, magazines, CDs, DVDs, nothing. It will all be online. And when I

interviewed him, he described how he himself had already cut out all tangible media in

his own life, how he basically lived his life off his I-Phone screen. He called it being

“media green”, because of course, from an environmental point of view, what he is doing

makes a lot of sense.

And maybe Steve Rubel is right. I kind of hope not. His digital dream sounds like

a nightmare to me. But here’s the thing. We already have lots of

studies that suggest that we don’t read words on screens the same way we read them on

paper, and our brains don’t process information in the same way. So trading paper for

screens represents something much more fundamental than just simply switching delivery

systems.

So we need to think about the implications of all this stuff. We can’t simply accept that

the changes that technology brings are inevitable. That is often the impression you get

when you listen to the true believers. But I think we can’t surrender to the machine that

easily, at least not before we ask some questions and understand something about the

road we are going down. Just because we can do something, doesn’t mean we should do

it. See, I told you I wasn’t very practical.

So this is a very idiosyncratic perspective. I’m not saying I have all the answers, or even

any answers, and you’re certainly welcome to disagree with me and raise those

disagreements after I’m finished here.

I’m currently exploring some of these ideas for a new CBC Radio series I’m working on.

As some of you know, a couple of years ago, I did a series called Spin Cycles which

essentially explored the nexus between public relations and the press. And since then,

I’ve continued to examine that nexus as it evolves.

And what I find most interesting about that evolution is how social media has helped

erode the power and influence of the press by reducing, and in some cases, eliminating,

the gatekeeping or filtering role that we have traditionally played. Social media is not the

only factor. There are others that I will get to in as minute, but the fact is, this decline of

the gatekeeper is a reality. And I think that has implications that need to be explored

before we fully embrace the new order. And that is what I’m planning to do in this

new radio series I’m working on, and what I want to talk to you about today.

So today, we’re going on a trip to a place I call World 2.0. It’s a place where

it’s okay to talk to strangers, where everybody is somebody’s friend, and where the

national past-times include blogging and flickering and twittering and digging.

Now World 2.0 is a big place, and we can’t visit all of it today, so we’re going to confine

our travels to just two places that I hope you’ll find interesting. And I’ve chosen them

because they are places where your world as public relations people, and my world

as a journalist intersect.. And they are called Journalism 2.0, and PR 2.0.

But I suppose before we depart we should just take a moment to review how this whole

2.0 world came about. Let’s look at the work that you do. Public relations is a big and

complex field, and I realize you do lots of things, and PR people get upset when I focus

on just one aspect of it, namely media relations. But the fact is for most of the past

hundred years, your main vehicle for communicating with the public has been us, in the

press. And the weapon of choice has, more often than not, been the press release. You

write them, we receive them, and then we decide if there’s anything in there we want to

share with our readers, viewers and listeners.

And that’s pretty much the way it was until the mid-1990’s, when we all got introduced

to something called the world wide web. Specifically, I’m talking about what we today

refer to as Web 1.0 applications. And by that I mean things like e-mail, and websites and

search engines.

And for people in my business, and for people in your business, Web 1.0 was an amazing

breakthrough. Suddenly, we had access to a world of information with just the click of a

mouse. We could write to each other and send documents without having to go to a post

office, and if we knew how, we could create a web page and post as much information as

we wanted, and the whole world was our potential audience. How did we ever live

without it?

It was fantastic, and we thought the world had changed. But in retrospect, it is now clear

that we were wrong. Web 1.0 allowed people like us, in the communications business, to

do our jobs better and easier, but it did not fundamentally change the nature of the job we

do. We were still the masters of our respective universes.

We still pumped out information to our audiences, and they received it. Yes, it

was more information, and we could reach more people more quickly, but those people,

our audiences, were still mostly passive receivers of that information. We talked to them.

And thanks to e-mail, their ability to talk back to us had gotten a bit easier, but it

was still fundamentally a one way conversation. And this is important, we could talk

to them, but they couldn’t talk to each other.

And then, about 5 or 6 years ago, it all began to change. Actually, the first big

breakthrough happened ten years ago with the development of software that allowed

everyone to publish on the web. You no longer needed to be an IT genius to convey your

thoughts to the world.

And these new creatures were called weblogs, or blogs, and they were the first shots in

the Web 2.0 Revolution. And they were followed, over the past few years, by video

sharing sites like YouTube, and social networks like Facebook, and podcasts, and open-

source sites like Wikipedia.

And these social media applications really are a game changer for those of us who

communicate for a living. Why? Because unlike Web 1.0, the relationship between us

and our audience has now fundamentally changed. In fact, it has been turned on

its head. The wall that has historically separated journalists from their readers, viewers

and listeners has broken down. The balance has shifted away from journalists and into

the hands of what American media critic Jay Rosen very cleverly calls “the people

formerly known as the audience.”, the people that Time magazine named as the Persons

of the Year a couple of years ago…”you”.

The conversation is no longer one way. They can respond to us as easily as we can talk

to them, and they can also talk to each other after we’ve left the room. That’s why it’s

called “social media”.

Now for those of you who have studied public relations theory, this is supposed to be a

good thing. Way back in the 1920’s, PR pioneer Edward Bernays was talking about PR

as a two-way street. And in the different models of public relations that people study in

university, the ideal model is supposed to be symmetrical PR, meaning that you talk to

the public, the public talks back, and you adapt your behaviour according to what

they’re telling you.

But of course, it hasn’t really ever worked that way. PR has mostly been a one way

street, the communication has been asymmetrical. Public relations has mostly been

about pushing out messages in one direction only, trying to sell the public more than

actually communicate with it.

And the media has been the same, maybe even more so. Yes readers can talk back to

their newspaper by writing a letter to the editor, but there’s no guarantee your letter will

be one of the lucky few the editor chooses to publish that day. Media owners profess to

care what their readers and viewers and listeners think, but that’s mostly because they are

trying to deliver those people to advertisers.

The modern mass media is a product of an age of scarcity. There are only so many

inches on the page, and so many hours in a broadcast day. Since the 1890’s, the front

page of the New York Times has boasted, “All the News That’s Fit to Print.

And one of the consequences of that economy of scarcity is that the media assumed the role of society’s gatekeeper when it came to information. After all, somebody has to make decisions about what is important enough to get into the newspaper or on the air. Somebody has to determine what’s “fit to print”. Many years ago, the American journalist and press critic A. J. Liebling rightly declared that “freedom of the press belongs to those who own one.”

Well no more. Don’t like the media you’re getting? Become your own

media . Welcome to what I call Journalism 2.0, where you no longer need to be a

billionaire media mogul to start your own online newspaper, and where the tools of

journalistic production now belong to just about everyone, where there are no limitations

on time and space; and where the motto for a world based on the economics of abundance

rather than scarcity, might simply be “all the news”.

It used to be said that journalists wrote the first draft of history. Well, now that more than

a billion people in the world have video equipped cell phones, the odds that a

professional journalist will be the first person to stumble upon a big story like a natural or

man made disaster are pretty slim. You just have to think of where the first images of the

tragedy in Mumbai came from last week, to realize how much has changed.

The first people to report on that story were people on the scene, sometimes even people

who were actually under attack. And they posted their stories, pictures, and videos on

blogs, or on YouTube or Facebook, or sent messages on Twitter. Or, they may have sent

them to any one of the many of so-called citizen journalism sites that have sprung up in

recent years; sites like NowPublic in Vancouver or Digitaljournal here in Toronto. Or

they might have gone someplace like CNN’s I-Reports, created by a mainstream media

outlet in order to get into the citizen journalism game. .

And what these citizen journalism sites have in common, is that they are all about

building a community with their audiences by allowing readers to determine which

stories are worth paying attention to. Got something to say, pictures or videos to share,

go ahead and post them on our site. It’s crowd-powered news.

We used to call those people in India “eyewitnesses”, and their evidence would be

aggregated and filtered by journalists, who would then produce what they considered,

based on their skills and experience, to be the best available version of the truth.

But it’s not like that anymore. The eyewitness has become a “citizen journalist”. And

there’s no editor telling that citizen journalist that their story’s not interesting or

correcting their grammar, or ordering them to lose a few hundred words, or asking who

their sources are, and there’s no lawyer warning them against possible libel suits.

In the mainstream media, we have to worry about all of that. It’s one of the things

that slows us down. We try to make sure we get the story right before we publish it. In

Journalism 2.0, it’s the other way around. If you make a mistake, your community will

supposedly tell you about it, but not until after it’s already out there. There are no

“gatekeepers” making decisions on what readers can or cannot see.

I like to call this new world Media Nation. It’s a place where almost anyone can “own”

their own press, where the power of elites has been diminished, where the voiceless have

found a voice, and where “the wisdom of the crowd” can prevail. Its potential impact has

been compared to the invention of the printing press in the 15th century.

And by and large, I think I think this is a good idea. How can you not be in favour of democratizing the media? But as someone who has been a gatekeeper in the mainstream press for more than two decades, I do have some reservations about Journalism 2.0. I think journalism is, by definition, a collaborative process that requires editorial input.

Somebody has to ask the question, “how do you know this is true”? In the absence of that, I’m not sure citizen journalism is actually journalism. And I worry about all that unfiltered, unmediated, unedited crowd-powered “news” that is floating around out there. How do we know what and whom to believe, and what is important? And who really benefits when the journalistic filter is weakened or removed entirely?

Have we as citizens and consumers become sufficiently sophisticated that we no longer need anyone to help us separate truth from spin in the marketplace or at the polling booth? Do we have the time and the energy to do that? Are we really entering an era of citizen empowerment, or will savvy corporate and political marketers simply find a way to co-opt these new tools, to shape the “conversation” to their own ends?

Now personally, I don’t believe the gatekeeper model will ever completely disappear. Many people, maybe even an increasing number of people, will want to get their news from these new non-traditional sources. A growing number of young people especially, now believe that the information they get on blogs and other online sources is just as reliable as what they get from the mainstream press, or at least, reliable enough.

But there will always be people who are looking for the kind of expert guidance through

the forest of information that only mainstream media can provide. And there will always

be a demand for the kind of investigative journalism that is critical for our democracy to

survive, but which is expensive and time-consuming. The challenge will lie in finding

new models to fund all of that.

And that’s a critical issue at the moment because the emergence of Media Nation is

occurring at a time when the business model for old school media appears to be broken,

perhaps irrevocably. That’s especially true for newspapers, especially in the United

States. Circulation, profits, revenue, employment, share price – have all been heading

downward for the past few years, but the pace over the past year or two has accelerated

dramatically.

And that’s even before the recent economic meltdown, whose impact on advertising

revenue we are just beginning to see. Just a couple of days ago it was announced that

newspaper ad revenue in the U.S. fell almost $2 billion or 18.1% in the third quarter.

Advertising dollars from the auto industry alone to all U.S. media outlets is expected to

decline by about $3 billion this year.

For those of us who are in the business, the rate of job loss is particularly troubling.

Twenty four hundred newspaper jobs were lost in the U.S. in 2007. In Canada, it seems

as if hardly a week goes by without some news of further lay-offs. This week it’s Rogers

Last week, 105 people at CTV. The week before, 560 at CanWest Global.

Now some of this decline can be linked directly to the rise of social media. Classified

advertising is clearly being lost to sites like Craigslist, where members of that community

can advertise for free. This has caused huge problems for newspapers. Classified

advertising revenue, which typically makes up about 30-40% of a newspaper’s ad base,

plunged more than 16% in the U.S. in 2007.

And there is no doubt that that’s a very serious problem, but I think only a cockeyed

optimist would believe that the solution to the woes currently besetting mainstream media

in general, and newspapers in particular, can be solved by selling more banner ads or

somehow “monetizing” more of their online content.

Because there are problems with mainstream media that are fundamentally non-economic

in nature that also need to be confronted. And among the most important of those are

issues of trust and confidence. We used to have it, now we don’t. Poll after poll has

found that people find media less credible, less honest, less fair, more biased, more prone

to errors, and less likely to admit making those errors, than even just a few years ago.

This is clearly a problem for an institution whose credibility is its only real currency. And in the days before Journalism 2.0, this would not have been a really serious problem.

So people didn’t like us, so what? What else were they going to do? Where else would

they go?

But now it does matter, because they can go to Media Nation where the rules of the game

have changed. Audiences there are no longer content to be passive consumers of news.

They want to be part of a “community” of journalists and other readers. And they are

much less willing to accept what they have been told by someone whose authority derives

solely from the fact that they happen to be employed by a mainstream media outlet.

As you know, over the past few years, as the popularity of social networking has

exploded, surveys have consistently shown that people are much more inclined to trust

members of their “community”, whether real or virtual, than they are people who have

traditionally worn the mantle of “expert”.

More and more, the professional filter is giving way to the social filter. In the 2007

version of their annual “Trust Survey” Edelman Public Relations discovered that the

answer to the question “who do you trust?” is increasingly, “people like me”. These are

the people whom the author Paul Gillin terms “the new influencers” –friends, neighbours,

and perhaps most importantly these days, members of various online communities.

Now these online communities can spring up anywhere. Trying to find them, let alone

being able to monitor them and communicate with them is a very difficult job, as you

know. It is perhaps the biggest challenge for what many people label PR 2.0 – public

relations in the age of social media. And what PR 2.0 has in common with Journalism

2.0 is that in both cases, the gatekeeper has been relegated to the back seat.

In PR 2.0, you can talk to your audiences directly, and they can talk back to you, and

perhaps most importantly, they can talk to each other. Say good-bye to that one way

street. And all these conversations can happen without having to go through the pesky

filter of the media.

The fact is that when you can talk to your audience directly, on their blogs, on Facebook,

on YouTube, on other social media, then you don’t need us as much as you used to. For

more than a hundred years, we decided what would get promoted and what wouldn’t,

what press release would get picked up, which photo opp. we’d cover, what product or

service we would give our third party endorsement to. You had to go through us to reach

your audience, and now, increasingly, you don’t have to. For years, PR has really been

about media relations. Now, more and more, it will actually have to be about public

relations.

Talk about transformative change! Let’s look at that staple of the PR industry –

the humble press release. As I mentioned earlier, for more than a hundred years, it has

been the main channel of communication between you and us. And it won’t be

disappearing anytime soon.

But here’s the thing about press releases. They are the ultimate symbol of PR’s one way

street. They are not designed to spark a conversation between an organization and its

public. They are a monologue, not a dialogue. So it’s not surprising that in an age of

social media, there are many people out there gunning for them.

The big buzz, as you know, is now around SMR’s – social media releases – designed to

get the conversation going, allowing readers to disseminate information, use multimedia tools, share the content, and spark other conversations. Today, about half of all online releases are read directly by the general public, thanks to online newsrooms, search engines and tools such as RSS.

And as with Journalism 2.0, there is much to like about PR 2.0. Why shouldn’t you be

able to talk directly to your audiences, and why shouldn’t they be able to hold you more

accountable? You are no doubt already aware of the challenges this poses. You know

that online communities are notoriously uninterested in being told what to think or what

to buy.

You know that companies and organizations no longer have as much control over their

corporate and brand reputations as they used to. You know that the social web is an

uncontrolled forum for the exchange of ideas and opinions. Anyone can write anything

they want about a company or a brand, any time they want. And if you’re not paying

attention, those comments can be picked up and spread around the world before you even

know they’re out there.

In the days of PR 1.0 it was largely true that brands were defined by what companies said

about themselves in their advertising, on their websites and in their press releases. Now

brands are in part defined by what others say in private, usually after the company and

their PR people have left the room.

And what those people have to say can be dangerous and unpredictable. The social web

audience is the toughest, most demanding, most unforgiving audience there is. You

ignore their opinions at your peril. They’re always on the lookout for signs that someone

is being less than transparent, less than authentic. Try pulling a fast one on them, as

WalMart famously did with their fake WalMarting Across America blog, and you will

pay a steep price.

On the plus side, a whole new world of opportunities can open up for clients prepared

to have meaningful conversations with online communities. But those clients will have

to be genuinely interested in learning what customers really think about them, their

products and their services, and then be prepared to do something to fix the problems.

Is PR capable of pulling this off? There are many skeptics. Jay Rosen, whom I

mentioned earlier, told a conference organized by Edelmans last year, that for PR to truly

embrace the potential offered by social media would be tantamount to asking it to change

it’s DNA. In other words, it’s not likely to happen.

And that skepticism is not just coming from the usual cast of the industry’s critics.

It’s not hard to find PR practitioners, writing on some of the very good PR blogs that are

out there, who aren’t sure that public relations is capable of listening and engaging the

public, of sparking conversations rather than simply pushing messages.

One British PR blogger wrote that the main problem is that PR’s priority will always be

to protect the interests of those paying the bill. Since PR has historically been part of the

problem, in the sense that it has helped create the distrust and suspicion that many people

feel towards business and government – how can it now be credibly seen as part of the

solution? She asks, “should PR not just accept that it is part of the bling put out by

organizations – it is just one sided publicity, spin, and propaganda?”

I know in earlier sessions here you’ve talked about the importance of establishing

relationships with bloggers. And I think that’s great. But let’s be honest about what is

really going on. At the end of the day, the question the CEO will be asking his or her

communications team is not how many online conversations they’ve been able to spark,

but how many bottles of beer, or cell phones, or computers they’ve helped to sell.

So I find it hard sometimes not to share the skepticism of the industry’s critics as we

move forward into a PR 2.0 world. As many writers have pointed out, social media is

about respect, engagement and transparency, and these have historically not been

qualities that PR has either embraced or practiced. I think the great worry is that the sins

of the old media will be visited on the new, that the tools of social media will be used to

accomplish some very old fashioned objectives.

And I’m not just talking about the very obvious ethical sins like setting up fake blogs or

using the anonymity of social networks to push messages, or paying bloggers for

postings. To be honest, I even get nervous when I see PR groups advertise workshops in

search engine optimization. Google, for example, was supposed to be based on the idea

of the wisdom of the crowd. You got ranked high on Google because members of that

community thought you belonged there, not because some clever people had figured out

ways to get you to the top.

One of those advertisements I saw recently proclaimed ..”the potential for

communicators seeking to reach audiences directly is staggering. If you can master SEO

and keyword usage, your news could go viral with the push of a button—especially if

you’re savvy about how you distribute your announcements.”

As I said, I understand that that is the business you’re in, and maybe I’m being paranoid,

but that kind of talk makes me nervous. To me, it speaks to the reason why we had

gatekeepers in the first place, and why I think they still have a useful role to play.

In a world without gatekeepers, we are required to make two assumptions. One is that

the people pushing their messages directly to the public will be honest and

straightforward about it, and two, that if they are not, the public will be savvy

enough, and engaged enough, to call them on it. I know that the true believers of World

2.0 believe we can count on that happening. I’m not so sure.

I said at the beginning that it is important to recognize that technological change is not

inevitable, but that’s not exactly true. PR 1.0 and Journalism 1.0 will not disappear, but

they are not the only game in town anymore, and they never will be again. And there are

lots of reasons why we should celebrate that fact. But I also said we need to understand

the implications of the road we are going down. And in a world without gatekeepers, it is

important that everyone involved understand that with great power comes great

responsibility.

And so what have we learned from our little tour of World 2.0? I think it would be fair to

conclude that it can be a pretty scary place. It’s scary for mainstream journalists like

myself to see the gatekeeping role that we have so long cherished and protected begin to

evaporate in the wake of this thing called Journalism 2.0.

And it can be scary for people who work in communications too. Driving on a one way

street is always easier than driving when traffic is moving both ways. And it’s always

easier to control messages then to open them up for comment and criticism.

But World 2.0 is also a very exciting place, filled with incredible possibilities. I’m excited by some of the experiments now underway that have professional and amateur journalists working together in collaborative projects that have the potential to produce excellent journalism. And smart people are thinking of new business models to replace the old one that is clearly no longer working.

And the potential for social media to bring people together and empower them

is enormously exciting. Look at how Barack Obama was able to use social networks to

create an online army of several million people in this year’s election campaign.

I know that many of you here today work in government communications, and I would

suggest you keep a close eye on the Obama administration’s plans to use social

media to ensure that both the quantity and the quality of communications between the

government and its citizens is richer and more meaningful than ever before. If they

succeed, it would be revolutionary

So whether you work in journalism or public relations, we are clearly at the beginning of

something very important and very exciting. The pace of change can sometimes be

dizzying. Just when we get used to everyone blogging, they start twittering, and who

knows what will be next. We need to go into it this with our eyes open, with an

understanding of how our behaviour has to change, and fully aware of where the potential

pitfalls lay. But there is no turning back. As we like to say here in Ontario: World 2.0:

yours to discover.

Have you ever been at the far end of the city from your home and wondered just how much a taxi ride home would cost you? It’s always nice to know the price of something before we decide to buy it. Taxi rides are one of those things that you can’t really estimate until the meter is running. Until now.

Have you ever been at the far end of the city from your home and wondered just how much a taxi ride home would cost you? It’s always nice to know the price of something before we decide to buy it. Taxi rides are one of those things that you can’t really estimate until the meter is running. Until now. Jordan initially developed the site using thetaxi fares for Ottawa, where the 76design office is. But he also included a straightforward way that anyone can customize it to calculate fares based on the city you live in.

Jordan initially developed the site using thetaxi fares for Ottawa, where the 76design office is. But he also included a straightforward way that anyone can customize it to calculate fares based on the city you live in.